Location & Continent

Continent: Asia

Country: China

Region: Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Ordos area)

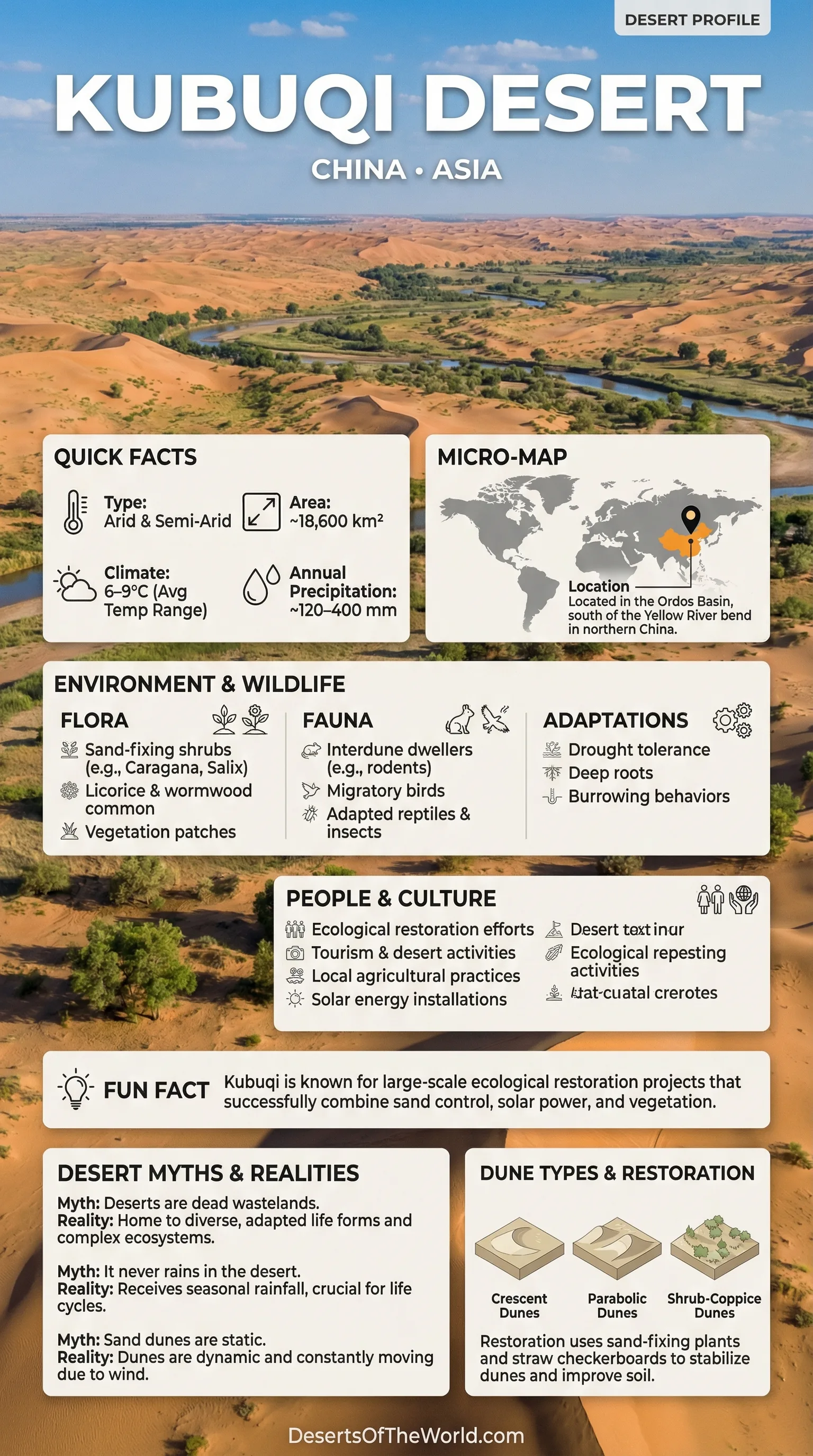

Broader Setting: The Kubuqi Desert sits inside the Ordos Basin, hugging the southern bank of the Yellow River and stretching between the Hetao Plain and the Loess Plateau.

Coordinates: 39°15′–40°45′N, 107°00′–111°30′E

Kubuqi Desert – Map View

Photos Of The Kubuqi Desert

Physical Features

Area: About 18,600 km²

Length: Roughly 400 km (east–west)

Typical Width: About 15–20 km in the east, widening toward 50 km in the west

Elevation: Commonly around 1,200–1,400 m

Dune Relief: Many dunes are 10–15 m high, while select dune faces can rise to around 90–110 m

Climate & Precipitation

Climate Type: Temperate continental with strong seasonal contrast

Rainfall: Roughly 120–400 mm per year, with most precipitation falling in summer

Temperature: Annual mean often sits near 6–9°C, while winters can be sharply cold and summers can feel surprisingly hot on exposed sand

Evaporation: Commonly far higher than rainfall, a key reason water is the main currency in this landscape

Ecological Setting

Ecozone: Transition between arid and semi-arid northern China

Biome: Deserts and xeric shrublands, grading into desert-steppe in places

Key Ecological Theme: Life clusters where wind slows, sand steadies, and thin pulses of moisture linger just long enough to matter

Plants and Wildlife

Sand-Fixing Shrubs Often Used: Caragana korshinskii, Salix psammophila, Hedysarum scoparium

Other Notable Plants: Artemisia ordosica and Glycyrrhiza uralensis (licorice) are frequently discussed in restoration work

Wildlife Pattern: In the Kubuqi Desert, animals tend to favor interdune corridors, vegetated patches, and river-near edges where food and cover are more reliable

Geology & Notable Landforms

Dominant Material: aeolian sand shaped by persistent winds

Dune Forms: Crescent dunes, parabolic dunes, compound dunes, and shrub-coppice dunes create a “moving architecture” of ridges and hollows

Special Note: The Kubuqi is often described as a rare active sand sea in this part of China, where dunes can remain mobile without constant new sand supply

Introduction To The Kubuqi Desert

The Kubuqi Desert is a wide band of sand in northern China that looks, from above, like a golden ribbon pinned to the curve of the Yellow River. It is not a single, uniform sea of dunes. It is a mosaic—open sand, shrub islands, firmer sandy ground, and occasional low pockets where moisture can briefly settle.

In global desert terms, Kubuqi sits in a transition zone. It is not as hyper-dry as the world’s most extreme deserts, yet it still behaves like one: wind is the chief sculptor, and water arrives in short, seasonal bursts. That combination makes the desert both delicate and responsive. Small changes in vegetation cover can shift the whole feel of the land.

Where The Desert Fits In The Ordos Landscape

The Kubuqi lies within the Ordos Basin, a broad structural lowland with a long history of sediment, wind, and river influence. To the north, the river and plains create a contrasting strip of greener terrain. To the south, the loess lands bring a different texture—fine dust soils that can stand like cake layers on cliffs, yet crumble into powder when disturbed.

This positioning matters. The Yellow River bend acts like a giant guiding rail for winds and sand movement, while nearby plateaus influence airflow. Think of it as a natural wind corridor with a sand floor. When gusts rise, dunes can behave like slow waves—subtle in a day, meaningful over years.

Core Measurements That Define Kubuqi

A desert can be described with poetry, but its numbers tell the backbone story. In the Kubuqi Desert, the key figures point to a long, narrow sand system—more like an extended belt than a round “desert blob” on a map.

| Metric | Typical Value | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Area | ~18,600 km² | Large enough for many dune systems and microhabitats to coexist |

| Length | ~400 km | Shows a strong east–west structure shaped by regional winds |

| Rainfall | ~120–400 mm/year | Enough for shrubs and grasses—if wind erosion is controlled |

| Dune Heights | Often 10–15 m, with pockets near 100 m | Tall dunes hint at long-term sand storage and active reshaping |

Notice what is missing from the table: a single “average” dune type. That is deliberate. In Kubuqi Desert terrain, variety is the rule, and averages can blur what makes the place readable on the ground.

Climate Rhythm: Short Wet Season, Long Dry Stretch

The Kubuqi climate runs on a simple beat: summer brings most of the rain, and the rest of the year is mostly about dry air and wind. Even when annual rainfall sounds moderate for a desert, evaporation is so strong that moisture can vanish quickly from the surface.

This is why timing matters for plants. A shrub in the Kubuqi Desert is built for patience. It waits, then moves fast—leafing out, flowering, setting seed—whenever the seasonal window opens. One year, a few storms can paint patches green. Another year, the same ground may look quiet and pale.

How Wind Builds A Sand Sea

In the Kubuqi, wind does more than push sand around. It sorts it like a careful hand sifting flour: finer grains travel farther, heavier grains hop and settle. Over time, this creates dune forms that repeat like patterns in fabric—ridges, bowls, and long scalloped edges.

Scientists describe multiple dune families here, from crescent-shaped dunes to parabolic dunes anchored by vegetation. There are also compound structures where dunes stack on dunes, making a layered terrain that feels almost like frozen surf. In some areas, shrub-coppice dunes form around hardy plants, turning a single bush into a sand-catching machine.

Soils: Mostly Sand, But Not All Sand Is The Same

Desert soil in the Kubuqi Desert is often described as aeolian sand, yet that label hides detail. Grain size, mineral mix, and how tightly sand packs can change from ridge to hollow. A few steps can shift footing from loose sugar-like grains to firmer, slightly crusted surfaces.

Where vegetation has taken hold, the sand can slowly gain structure. Organic matter is usually scarce, but even small inputs—fallen leaves, fine roots, microbial films—help bind particles. It is a quiet process, almost invisible. Still, it can be the difference between a dune that slips with every gust and one that stays put for seasons.

Vegetation That Makes Stability Possible

In many parts of the Kubuqi Desert, the most influential plants are not tall trees but shrubs and tough grasses. They work like natural netting. Stems slow the wind near the ground, leaves catch drifting grains, and roots stitch the sand together.

Several sand-fixing species are widely discussed in restoration studies, including Salix psammophila, Caragana korshinskii, and Hedysarum scoparium. Add plants like Artemisia ordosica and licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis), and you get a toolkit of vegetation suited to dry, windy ground. Each species plays a slightly different role—some anchor dunes, some enrich soil, some tolerate cold snaps with ease.

One of the most interesting details is how plant cover creates microclimates. Shade lowers surface heat, wind slows, and moisture lingers a bit longer. A patch of shrubs can feel like a small room in an open-air house—still sandy, still dry, but more accesible to life.

Water In A Desert Beside A Great River

It sounds like a contradiction: a sand sea beside one of Asia’s major rivers. Yet that edge is part of what makes Kubuqi distinctive. The Yellow River provides a regional water presence, but it does not automatically hydrate the dunes. Sand is porous, and surface water can be difficult to hold without vegetation and careful management.

In practice, water appears in many forms—seasonal rainfall, shallow soil moisture after storms, and localized wet spots in low areas. Some research in the region also focuses on how restoration changes evaporation and water balance, since more vegetation can mean more transpiration. That trade-off is central in dryland restoration: the goal is stability and biodiversity without overstretching limited water.

Restoration As A Long-Term Landscape Project

The Kubuqi is frequently mentioned in global conversations about land restoration because it shows how multiple approaches can be layered: sand-fixing plants, managed land use, and modern infrastructure that fits desert conditions. It is less a single project and more a long sequence of decisions that build on each other.

One important theme is the shift from moving sand to a more structured surface where dunes are steadier and vegetation cover is higher. That does not mean the desert disappears. It means the terrain becomes more predictable, with more patches that can support plants, wildlife, and desert-adapted activities without constant re-burial by windblown sand.

- Sand Fixation: Shrubs and grasses are placed to slow near-ground wind and catch drifting grains.

- Edge Stabilization: Protective belts are often used to limit dune movement into vulnerable margins.

- Soil Improvement: Over time, roots and litter help develop a thin, living layer that supports more plant variety.

- Monitoring: Satellite data and field stations track vegetation change, dune movement, and water stress.

Solar Fields and Sand Control Working Side By Side

Kubuqi has also become known for large solar installations placed across sections of dunes and sandy flats. In a desert, sunlight is a dependable resource, and flat sandy terrain can host long, linear solar corridors. It is a striking visual: dark panels laid over pale sand, like a shadow stripe drawn across the land.

Beyond electricity, solar fields can have physical effects on the near-surface environment. Rows of panels can slow wind at ground level and create shaded strips where surface moisture evaporates a bit more slowly. When paired with vegetation work, this can support a more stable surface in some areas. The result is not a “new forest” replacing a desert. It is a hybrid desert landscape where energy infrastructure and ecology are designed to coexist.

Places Where Life Concentrates

The Kubuqi Desert is easiest to understand by looking for edges. Life gathers where conditions soften: the borders near river-influenced plains, the sheltered faces of dunes, and the interdune lows where fine material and moisture collect. These are the desert’s “pockets,” small zones where plants can seed and animals can find cover.

Some areas include lakes or wetland-like patches at the desert’s margins, and there are also sites where research has focused on changing ecosystem patterns over time. This edge-driven ecology is common in deserts worldwide. Kubuqi is a clear example: it is not only about dunes, but also about the subtle spaces between dunes.

Why Kubuqi Matters In Desert Science

Deserts are often labeled empty, yet they are full of process. The Kubuqi Desert is especially useful for understanding how wind, vegetation, and land management interact in semi-arid conditions. It is dry enough that dunes can stay active, but wet enough that restoration can measurably change the surface within human timescales.

That balance makes it a living case study for topics like dune morphology, shrub-based sand fixation, and water-aware restoration planning. When researchers map dune types, track vegetation cover, or model surface temperature changes from planting, they are reading the desert like a book—page by page, season by season.

Sources

NASA Earth Observatory – Building A Great Solar Wall In China (Kubuqi Desert)

United Nations Environment Programme – Review Of The Kubuqi Ecological Restoration Project (PDF)

UNCCD – The Kubuqi International Desert Forum (Event Page)

Chinese Academy Of Sciences (IGG) – Researchers Uncover Kubuqi Desert Environmental Change

Yale University – Response Of Surface Temperature To Afforestation In The Kubuqi Desert (PDF)

ScienceDirect – Ecological Restoration And Ecohydrological Change In The Kubuqi Desert